Discover the Huge Hoard of Iron Age Treasure Found in Yorkshire

Britain's largest hoard of treasure from the Iron Age has recently been unearthed in Melsonby, North Yorkshire

Picture the scene – you’re making your way through muddy fields in a quiet corner of the very top of North Yorkshire, scanning the ground with your metal detector like you’ve done countless times before. Suddenly, the sensor goes berserk and after doing some digging, you know you’re onto something big. But who to tell? This was when metal detectorist Peter Heads gave Iron Age specialist and head of archaeology at Durham University Professor Tom Moore a call.

‘The reason he called me is because I was doing geophysical surveys and had an archaeological research project in the area near Stanwick, which is a big Iron Age power centre in North Yorkshire,’ Tom explains. ‘He’d dug a couple of holes and I could see that he’d got into archeology (so not just top soil), and I could also see that there were a couple of objects and that they were likely Iron Age.’ When multiple prehistoric objects are found together, they’re officially considered treasure and need to be assessed independently before further work can be done.

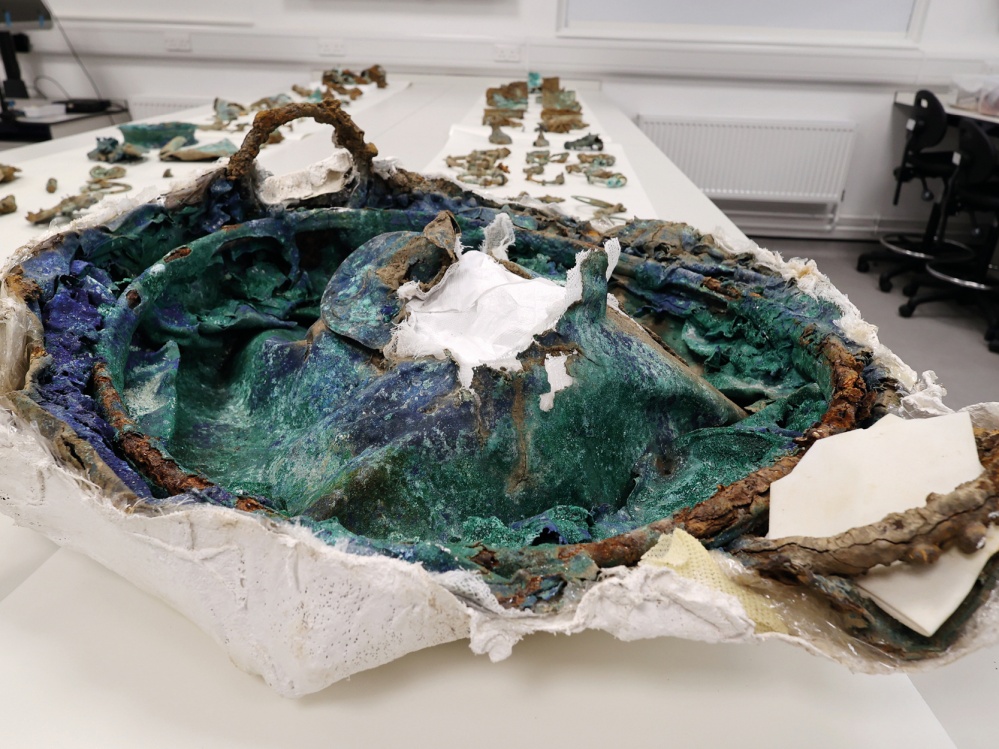

Sensibly, the detectorist Peter had known to stop digging when he suspected he’d stumbled onto something significant. ‘That was excellent, because he knew not to dig it out we didn’t lose any critical information,’ says Tom. When Tom came to the site with a team of experts it slowly became clear how monumental the discovery was. ‘You could see there was a pile of copper alloy objects which were Iron Age in date which was already exciting. It was only when we opened the trenches up and started digging ourselves that we realised what he discovered was the merely the top of two huge deposits.’

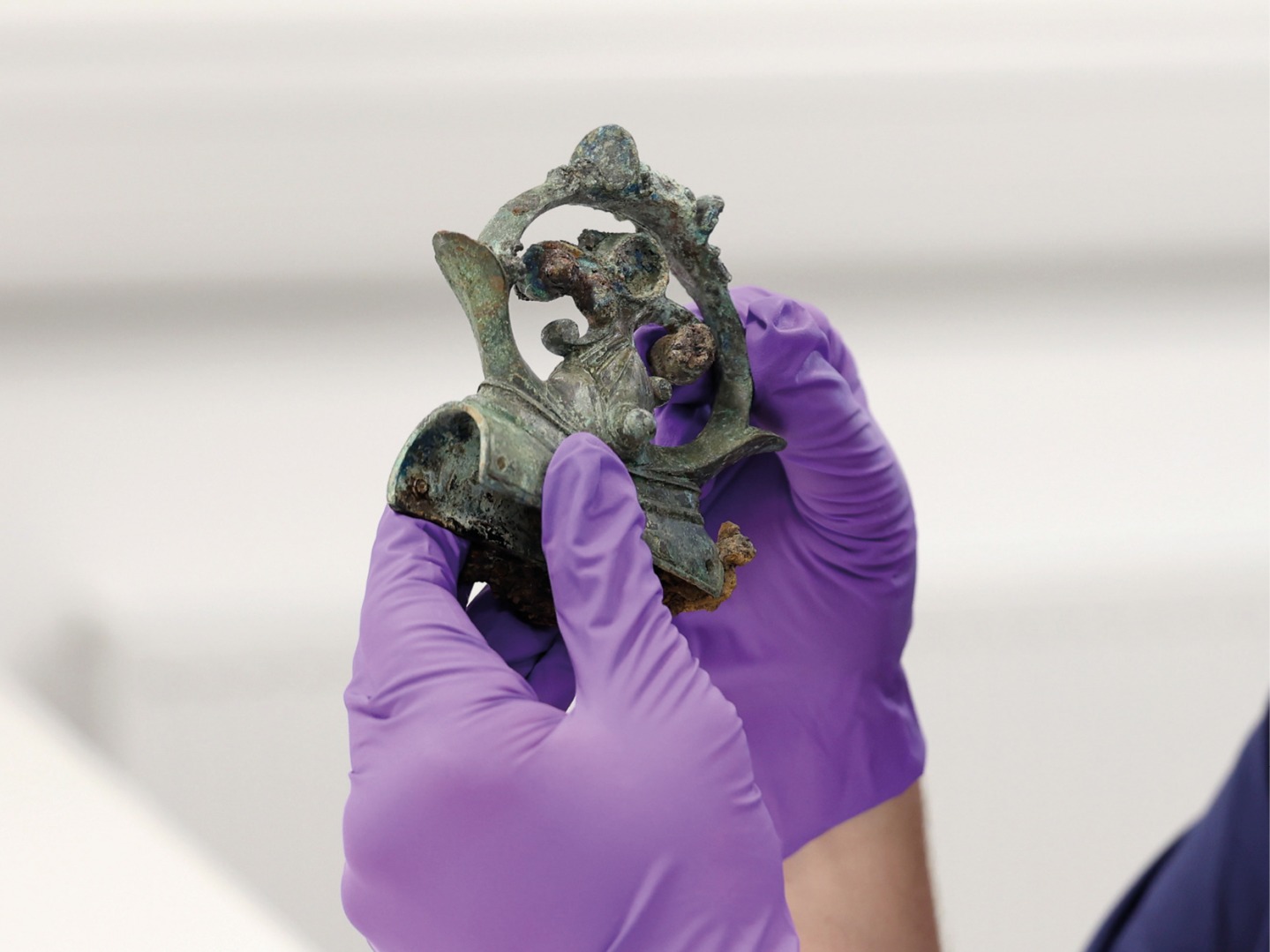

In total, more than 800 items have been recovered – a groundbreaking volume for Iron Age material in Britain. ‘That amount of material is just unprecedented,’ Tom says. ‘And we kept finding objects we were not expecting.’ The collection is incredibly varied, including bridle bits, linchpins, rein rings, harness fittings and cauldrons found within a cluster of iron tyres from chariots and other horse-drawn vehicles, all featuring stunningly intricate metal work and craftsmanship.

Even more interesting were the pieces that the team couldn’t identify, and those that had never been found in Britain before. ‘We have these big chunks of iron which look like bits of vehicles we haven’t seen before,’ Tom explains. ‘If you ever see a picture of an Iron Age chariot it’s like a buggy. These bits of vehicles are much chunkier and it looks to us that some of these are from wagons which we’ve never seen in the British Iron Age, so that’s another thing which has got us very excited. There are also some things which frankly, at the moment, we’re not sure what they are!’

Interestingly, the collection was split into two deposits, one being much larger and the second being smaller and more neatly placed together. Extracting these was a delicate process and raised fascinating questions about their purpose. ‘That [second] block is much more discreet and was probably wrapped as a bundle. Whereas the bigger deposit was a heap of stuff piled up, this smaller one is somebody wrapping stuff in textiles and then depositing it in another ditch. There is similarity in the objects between them, and they happened around the same time, so we suspect they might have been part of the same process.’

Iron Age is a term most of the public have heard of before, but a real understanding of what that means, and the ability to imagine what life was like for people at the time, is not as common. Roughly, the time period falls within the few centuries leading up to the Roman conquest of Britain which took place around the middle of the first century.

‘Bearing in mind the Romans didn’t get to northern Britain until a few decades afterwards, most people at that time in Yorkshire and the North East were farmers,’ says Tom. ‘They were living in farmsteads together, farming and keeping sheep and cattle – that’s what most people at the time did.’ That’s not to say however, that life was simple or isolated. ‘It’s clear that they were part of a much larger social organisation. Rural farmers were engaged in the wider community, they were exchanging and trading things like salt which comes from the coast in the North East, and millstone which comes from the Pennines,’ explains Tom. ‘We can see that these people were not living on their own. They were part of a largely occupied and highly-farmed landscape across the North and up into the Cheviots.’

In fact, we even know the name of this interconnected northern community thanks to Roman writers at the time – the Brigantes. ‘We think these people were unified together as this overarching group. The centre for that group of people was probably Stanwick, very close by where we made this discovery. We believe part of the reason why it’s there is because the people who were living at Stanwick were probably the elite of this much larger group of Brigantes. The Brigantes likely stretched over much of what is now Yorkshire and all the way up as far as Newcastle probably.’

But what significance does the treasure at Melsonby hold for our modern understanding of the Iron Age North? ‘As Iron Age specialists, we had an inkling that people at Stanwick were just as wealthy, just as powerful and just as networked as their counterparts in the South East. But sometimes there hasn’t been the level of research to back this up,’ Tom explains. ‘This is the largest hoard of Iron Age metal work ever found in Britain, and the fact that it comes from the North just emphasises to us, and to the general public, that the communities of Northern England were just as powerful.

‘There were incredible craftspeople around and if you look at some of the quality of these objects, most of them were made here by incredibly sophisticated metal workers. These people had the ability to make beautiful objects and they had an incredibly sophisticated network of interactions to get the material to do it.’

Although more research is needed to fully grasp the significance of the find, Tom and the team at Durham are eager for the public to be able to access it as soon as possible. ‘The Yorkshire Museum are doing a fundraising campaign to acquire the collection. It’s really a delight because the collection will stay in the region. It’s from Yorkshire and will stay in Yorkshire,’ Tom says. ‘They’ve already put some pieces on display and you can see them as a taster. There’s some nice bits so that people can get a sense of what’s there. What’s going to happen is that we’ll work with the museum on the conservation because a lot of it needs cleaning. As we do that, we’ll also do scientific analysis on how the metals were made, and where some of the materials come from.’

It can be difficult to see how the study of archaeology continues to hold significance for life today until discoveries like this happen. For Tom, understanding the past allows us to tackle problems in the present. ‘Archaeology can tell you about where we come from,’ he says. ‘On a broader scale, archaeology is working around issues like climate change. We can see how societies and communities have adapted to climate change in the past, from the crops they grew to the way they lived, and that’s really important to inform how we can then think about the impact of the climate now.

‘People have this idea that way back in the Iron Age, the Cheviots were wild landscapes – they weren’t. They were farmed landscapes, with probably more people living there then than there are now. I think it’s really important for people to understand where they live and how it’s changed. On a local level, [the treasure] reminds people of the heritage of this region, that it’s significant and that we should be proud of that.’