How Kielder Salmon Centre are Bringing Mussels Back

Home to the second largest population of critically endangered fresh water mussels in England, the North Tyne River and River Rede are crucial areas for this tiny ecosystem hero to make a comeback

When you think of rural Northumberland, plenty of wildlife springs to mind, from foxes and squirrels to deer, owls and kestrels. But hidden in the rivers and streams of Northumberland, you’ll find another local inhabitant whose role in our ecosystem is every bit as essential – the fresh water pearl mussel. But these hardworking creatures are under threat.

‘They are critically endangered and in decline for a lot of different reasons,’ Ben explains. ‘In general it’s to do with land use. You’ve got structures within the river which change the flow, you’ve got lots of gravel extraction and use of material from the river where the mussels live, and you’ve got barriers that affect migration of the host species (the mussels rely on a host during their larval stage). Then changes in land use often result in loss of sediment which the mussels also rely on. As a result, a whole cohort of juveniles can go missing or are wiped out.’

This is where Kielder Salmon Centre steps in. Since it was originally built, the centre has worked hard to help local wildlife thrive, beginning with salmon and now also including trout and fresh water pearl mussels. ‘When Kielder was created, a mitigation for the lost salmon was the Kielder Salmon Centre,’ Ben explains. ‘There was an agreement where the Salmon Centre would produce about 160,000 fish per year using wild stocks to mitigate for the loss of the spawning ground where the reservoir is.

‘This has opened up a really nice opportunity because it means we have the skills and knowledge for rearing the salmon and have extended that to trout, and in more recent times to the freshwater pearl mussel. The facility has opened up the opportunity to run the captive breeding programme, and to try and address these issues.’

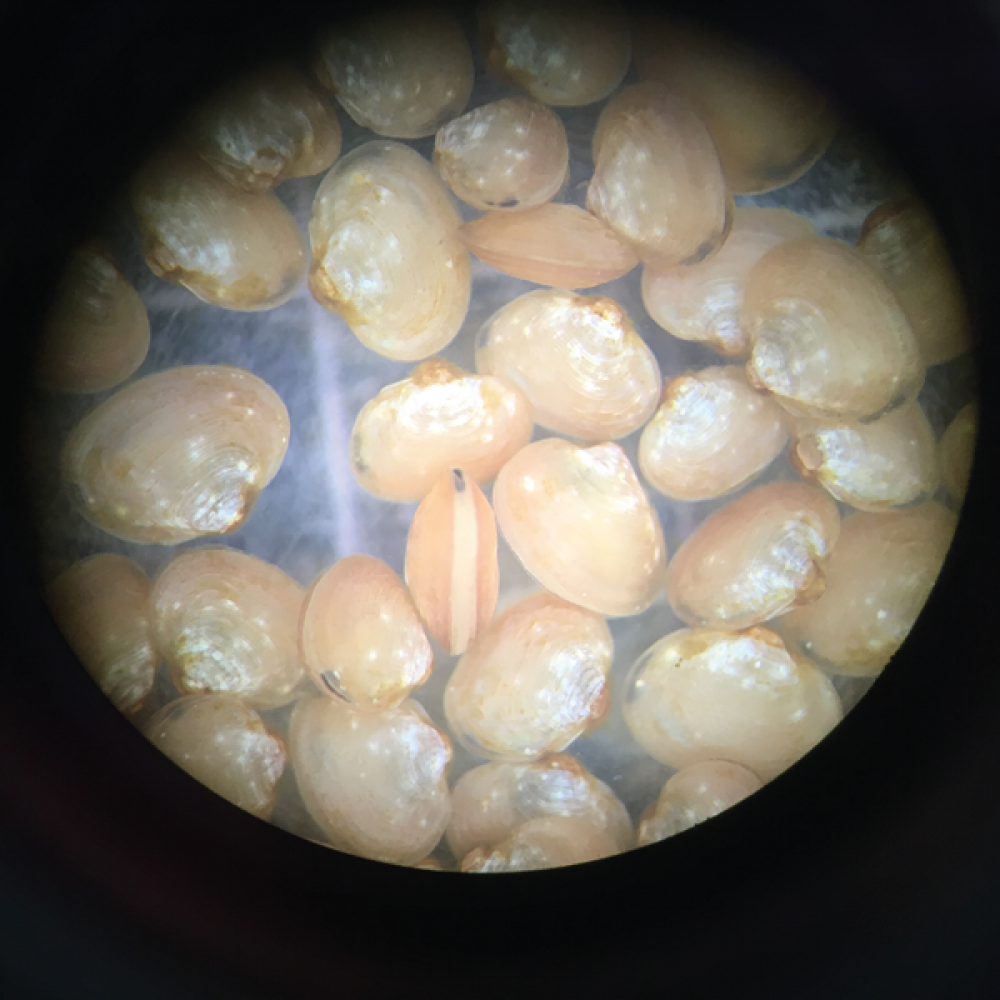

A day in the life at the Salmon Centre is far from glamorous, but caring for the next generation of mussels (on top of the fish) is non-stop. ‘When it comes to mussels, every Monday, Wednesday and Friday we will empty the nets on the tank where we have the host fish. The juvenile mussels that come off the host fish will be collected in these nets and I’ll go through them and remove any fish waste and put those mussels into incubator boxes, change the water and feed them,’ Ben explains. ‘Again I’m looking to see if they’re growing, and if they’re looking healthy and for any mortalities. That will continue for some months, and years, depending on the method. When they’re big enough they’ll either go to another system, which we call a floater system – it’s like a little in-house river where they’re kept in boxes – and we can keep an eye on them for a couple of years until they’re bigger and more durable. Then we can put them back in the river.’

The team have continued to improve the method of supporting the mussels throughout their life stages, which is a year-round process. Whilst the team monitor and support the early life cycle of trout from early January to summer, during July they hold onto some trout and head out into the rivers to search for fertilised female mussels. ‘I don’t have a way of opening them so what I do is collect a few and gently warm them up,’ Ben explains. ‘They release their larvae, and then I look to see if they’re viable. I bring them back to the facility and we put them in the tank with the fish for a couple of hours and the larvae will attach onto the gills of the trout. The gills move over the mussel larvae and the mussels stay connected to, and feed off, the fish – it doesn’t seem to negatively impact the fish.’

To some this may seem to be a lot of effort for little impact, but mussels are a crucial part of the river’s ecosystem. ‘I’d expect to see fresh water pearl mussels in an upland stream that’s slightly acidic, low in nutrients and often where it’s highly oxygenated,’ Ben tells us. ‘These mussels like to be behind what we call a stabilising boulder – a boulder that holds the riverbed together. At the back of that you get this really nice mix of gravels that are washed there by the water, and pinned down behind this boulder. Really this clear upland oxygenated water should be rushing through the gravel, keeping it fresh and clean.

‘The mussels are half a millimetre big when they come off the fish, so they fall and land on this gravel patch and dig down around 20 centimetres into the ground. At first they feed with their foot, but as they get bigger they start to transition to feeding with their gills. As filter feeders they gather the nutrients and organic matter that’s passing by, process that and release faeces which provides a valuable source of food for other creatures. Their feet dig down and they oxygenate the gravel with their body, plus their shells provide habitats for other creatures to live on like little limpets. If you get hundreds of mussels together, you get what’s called a mussel bed, and this in itself acts as a stabilising boulder. So you’ve got food processing, oxygenation, river stabilising and habitat creation.’

Mussels can also be used as a natural indicator of water quality – a healthy population of mussels makes for a healthy river. ‘In Poland they attach these little sensors and the mussels shut when the river is bad and they open when it’s good. If the population is not recruiting [adding to itself unaided] then we know, as efficient as they are, something is not working,’ Ben says.

Each facility across Europe has different short- and long-term goals for their programmes. ‘We all have different problems and different systems. [In Northumberland] we’ve got better at getting the mussels onto the host, we’ve got better at collecting them in the wild and getting them off the fish – we just need to get a little bit better at the incubator stage to get more of them through that. Once we’ve got that, we’ll have better numbers to release. In terms of the breeding programme, that’s our next win,’ Ben explains.

‘For me, a win would be to see the river naturally producing its own juveniles. What we don’t see is a young cohort, partly because they’re really small and hard to find, but partly because when we have looked closely, we don’t find the juveniles where they should be. Success is two pronged: one would be a continued improvement in our output of mussels, and the ultimate goal is to see the natural recruitment return and the key stressors mitigated or eliminated.’

With so much work still to do, the best way the public can help is by being informed about the laws protecting mussels and how to avoid inadvertently impacting any mussel populations. ‘Basically you can’t kill or disturb or move anything concerning mussels without permission,’ Ben explains. ‘Whether you’re causing damage knowingly or unknowingly, it’s best to just have an awareness that they’re there and there are experts you can call for more information.’