The Great North Road: London to Edinburgh – 11 Days, 2 Wheels and 1 Ancient Highway by Steve Silk (Summersdale) is available from all good retailers.

Join Our World... Sign up for our exclusive newsletter.

Be inspired every day with Living North

In the year the A1 celebrates its 100th anniversary, journalist Steve Silk decided to cycle the route of the old Great North Road, sticking as closely as he could to the old road and following in the footsteps (or tyre tracks) of author Charles G Harper, who published his own book about the road in 1901. In this exclusive extract, we join Steve on his journey from Boroughbridge towards Northallerton.

Boroughbridge breaks the Great North Road mould by keeping its High Street hidden from the main drag. Only the coaching inns were on this thoroughfare, but they were at the centre of an unlikely hub. Making my journey from London to Edinburgh, I’m inclined to forget that there were other coaches heading for other destinations. The North Briton, The Phoenix, The Diligence, The Expedition and The Defence all ran from Leeds to Newcastle via Boroughbridge; The North Star went from Leeds to Edinburgh; the Rapid from Harrogate to Thirsk and the Union from London to Newcastle. Finally, the Royal Charlotte from Leeds timed its services to meet both Newcastle and Glasgow coaches in this otherwise inconsequential town. The Crown was at the centre of the web. It’s another classic coaching inn which has managed to retain its original footprint. I once stayed here on a cold February evening when snow fell unexpectedly during the night. Cars were banished, twenty-first century sights and sounds disappeared under a cloak of white and were it not for the presenter of Stray FM reading out the school closures, we might have been enjoying our bacon and eggs in Dickensian times. It was wonderful in every way.

But this time I don’t even stop for a courtesy coffee, heading instead for the bridge over the River Ure – site of the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322. Like Empingham back in Rutland, this battle took place directly on the Great North Road. The Earl of Lancaster, rebelling against Edward II, was caught in a pincer movement between the king heading up from the south and a force led by Sir Andrew Harclay coming down from the north. Harclay’s men blocked both the bridge and a nearby ford. Lancaster tasked the Earl of Hereford with taking the bridge. But, in an incident worthy of Horrible Histories, Hereford was killed by a pikeman hidden under the bridge who managed to thrust his spear directly up Hereford’s backside. It wasn’t a great omen. Many more men were killed before Lancaster managed to negotiate a truce. And even that proved short-lived. He was later beheaded at Pontefract Castle, with 30 of his followers punished in the same way.

Immediately to the north of the bridge, the Great North Road traffic used to turn right. Nowadays we turn left because the old route lies obliterated under the runway of Dishforth Airfield. The full irony only becomes clear as I cycle along its western perimeter a few miles later. In recent years the airfield itself has become obsolete with weeds poking up through the concrete. So an abandoned Great North Road now lies under an abandoned Second World War airstrip. Perhaps I was paying too much attention to old ghosts here, because the next thing I know I’m on a dual carriageway heading for Thirsk. At Junction 49 it’s easily done. For a scary mile and a half I survive on a hard shoulder before re-joining the original Great North Road at Topcliffe which surprises me by calling its High Street ‘Front Street’. To me, Front Streets belong to the North East of England, preferably County Durham. Topcliffe is very much in North Yorkshire, but the road sign suggests I am making good progress. I remember the village for another reason too. While I exercised the MAMIL’s God-given right to do slightly geeky leg stretches against the Methodist church railings, I see my first swifts of the summer screeching overhead.

‘Aye, they’ve been here a few days now,’ says a neighbour. ‘Where are you heading?’

‘Northallerton – and I’m starving.’

‘Northallerton? Get yourself down the carvery at The Golden Lion. You canna go wrong.’

Summer’s here, the swifts have arrived and there’s decent food down the road. Excellent.

Somewhere around here the traveller leaves the Vale of York for the Vale of Mowbray – and crossing the River Swale at Topcliffe feels as appropriate a boundary as any other. While the Vale of York is seen as an area of intensive arable farming, the Vale of Mowbray has a more intimate scale. One gets the impression that while the tourists head for the high ground of the Dales and the Moors, the locals here are happy to get on with their farming out of the limelight.

To the west of the Swale, the modern A1 temporarily follows the line of Dere Street – the Roman road which ran from York to Scotland through places like Catterick, Bishop Auckland and Corbridge. Running north-west rather than north, it is nevertheless dead straight. Meanwhile the original Great North Road stays to the east of the Swale and looks almost entirely unmodernised as I cycle on.

‘The remaining 19 miles to Northallerton scarce call for detailed description,’ wrote Harper.

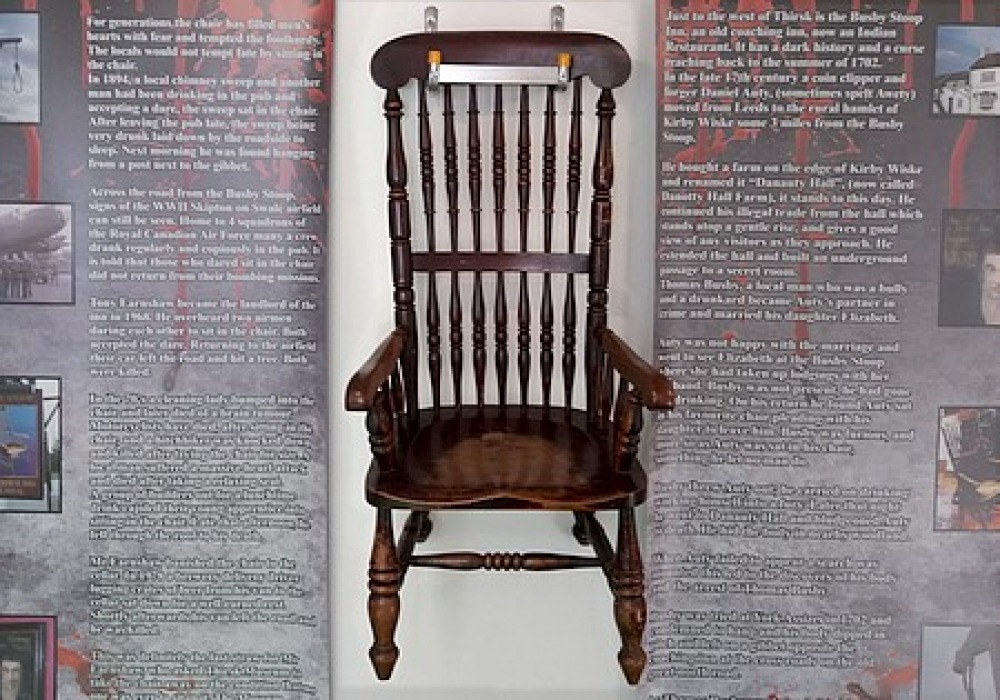

I have to disagree. The first junction of note is a roundabout with a petrol garage on one side, an Indian restaurant on the other and an unusual name on the map: Busby Stoop. Behind those two words lies a grisly folktale dating back more than 300 years. The restaurant was, until very recently, a pub. And in 1702 the landlord was Thomas Busby, a small-time criminal who had married Elizabeth Auty, the daughter of the notorious counterfeiter Daniel Auty of Danotty Hall. Father and son-in-law initially got on well, but later fell out. And one day when Busby returned to his pub the worse for wear, he found Auty sitting in his favourite chair threatening to take Elizabeth back home. There are numerous versions of what happened next, but the most succinct summary I’ve found comes from journalist Chris Lloyd in a feature for The Northern Echo newspaper:

‘Thomas ejected Daniel from both chair and pub and later that night crept into the counterfeiter’s house and bludgeoned him to death with a hammer. Busby was found guilty of murder and forgery and ordered to be hanged on a gibbet to be erected on the crossroads outside the pub, his body having been first dipped in tar to prolong its decomposition. Before the execution, Thomas was allowed a final drink in his favourite chair. As he left for the hangman’s noose, he cursed the chair, saying anyone who sat in it would suffer a premature, painful end.’

Curiously, the tale then takes a 200-odd year breather before a chimney sweep sat in the chair in 1894 and was found hanging from the original post (or stoop) the next day. But the legend really took off during the Second World War when the pub – already renamed The Busby Stoop – became popular with Canadian airmen based at nearby RAF Skipton-on-Swale. Locals said that RCAF aircrew who sat in the chair never came back from their bombing missions. From then on the story kept growing.

Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s there appeared to be a rash of strange tragedies. And when a young builder died after being cajoled into sitting in the chair by his mates, the landlord Tony Earnshaw banished it to the cellar. The final straw came when a delivery man tried it out down there – and died in a road accident soon afterwards. In 1978 Earnshaw donated the accursed chair to a museum in the nearby town of Thirsk – with strict instructions that no-one should sit in it.

Busby’s chair is now to be found at the community-run Thirsk Museum. Until relatively recently, it was rather hidden away, suspended from the ceiling in the kitchen section, a little out of sight, out of mind. But in 2018 it was moved to pride of place in the front room – hung high on a wall. Crucially no-one is allowed to sit on the chair – not even the Japanese film crew who had travelled thousands of miles thinking they could do just that. I visited the museum once and couldn’t resist asking the volunteer guide if, really, it wasn’t a load of old nonsense.

‘Well, most of those deaths do seem to be coincidental,’ she said.

Then she fixed me with a rather beadier eye.

‘But on the other hand, there do seem to have been rather a lot of them.’

I paused, not knowing whether to push the point.

‘Put it like this,’ she continued. ‘Last winter when it came off those hooks I was happy to polish it, but silly as it sounds, I certainly didn’t sit on it.’

Something makes me want to return to the Wear before I get the bike out. The tall Croxdale Viaduct takes the East Coast Main Line across the river to the west, while the modern road eases past to the east. The original Sunderland Bridge has a more human scale, allowing me to look down on the boulders breaking the water’s flow, the spume bright-white in the morning sun. I take a deep draught of northern air. It’s good to measure my progress from an ancient bridge spanning a timeless river. And of course it’s another opportunity to appreciate that all I’ve got to do today is cycle from A to B.

I start pedalling. This part of County Durham used to be a nightmare for coach drivers. A sharp turn to get onto Sunderland Bridge had been identified as an accident blackspot after an incident in 1815. Six years later, two passengers died when they were flung over the bridge from the outside seats of a mail. Eye-witnesses told how the coach driver James Auld had whipped the horses too hard and taken the bend too fast. He was later found guilty of manslaughter for ‘driving furiously and unlawfully’. Auld later insisted that he too went flying over the bridge’s parapet and only survived because he hung onto his reins, waiting to be rescued. Admittedly our main source for that aspect of the tale is Auld’s alcoholic son who spoke to a writer in Darlington some years later. ‘He repeated the story,’ recorded Samuel Tuke Richardson, ‘whilst weeping copiously on my bosom in Blackwellgate’.

Having crossed the Wear at Sunderland Bridge, the coachmen crested one more hill to find the same river in front of them at Durham. The Wear is one of the Pennine rivers not to get the memo about heading west/east, putting in some stubborn Northern twists in this neck of the woods. But this last hill allows me to freewheel down to the suburb of Old Elvet, where Durham University is busy spending millions on new buildings – including the Bill Bryson Library, I notice. Harper, writing at the turn of the last century, and feeling rather grumpy at this juncture, wouldn’t have recognised it:

‘Besides being dirty and shabby it is endowed with a cobble-stoned road which, as if its native unevenness were not sufficient, may generally be found strewed with fragments of hoop-iron, clinkers and other puncturing substances calculated to give tragical pauses to the exploring cyclist who essays to follow the route whose story is set out in these pages.’

There were plenty of tragical pauses for car drivers as the twentieth century wore on, simply because the medieval bridges couldn’t handle the volume of modern traffic. Durham Cathedral is built on a tight loop which means that the Wear has to be crossed twice more. The 1960s Millburngate Bridge and the 1970s New Elvet Bridge have partially relieved the pressure, leaving the originals free for pedestrians and cyclists.

Crossing Old Elvet Bridge plunges me into the heart of the city which instantly screams ‘world heritage site’ by the sheer number of international tourists and food outlets. After hundreds of miles of “normal” England, it’s quite a culture shock.

For a start it’s noisy – not least because my later start means that the tourists have arrived. A large block of flats is going up alongside the river. The builders’ drills in the distance compete with the chatter of different languages on the streets. An attention-seeking busker tries to belt out ‘Hey Jude’ above the hubbub. Nothing remotely unreasonable, but nevertheless an assault on my senses compared to previous days. I start by climbing Saddler Street, colonised by every restaurant chain you’ve ever heard of and some you perhaps haven’t. I’m now approaching the centre of this near-island, where some sort of elemental force seems to drag all of us visitors up the hill.

The legend of Durham centres around St Cuthbert who died on Lindisfarne Island – some 80 miles further north – in 687. When it later came under threat from the Danes, the monks fled, taking Cuthbert’s remains with them. After seven years of wandering they first settled at Chester-le-Street before moving to Ripon in North Yorkshire. It’s when the monks were meant to be returning to Chester-le-Street in the late 10th century that they diverted here. The legend says that the cart carrying the coffin suddenly stopped after their bishop had a vision of Cuthbert demanding to be taken to ‘Dunholme’. No-one had heard of the place, but then a girl walked by and asked a woman if she had seen a lost cow. The woman said she had seen the beast heading toward Dunholme. The monks duly followed her to this impressive peninsula, where steep gorges provided natural defences against any foe. The remains of St Cuthbert have lain largely undisturbed ever since.

The road gets steeper, narrower and consequentially darker. I’m walking with the bike, but the tyres still judder along the cobbles of Owengate. Slowly the shape of the cathedral reveals itself – first the two western towers, then the rest of this exceptional building along the far side of a closely-mown green. Initially I take this as the classic cathedral close. But once I’ve reached the plateau I realise that Durham takes it one stage further with a castle – now part of the university – sharing the high ground. Living near Norwich, I’m used to the tranquillity of such a close. This one feels different. Between cathedral and green a dozen film wagons form a community to themselves, protected by guards in day-glow orange. Students intermingle with us tourists and, off to the left, a gaggle of Deliveroo riders are being raucously slapstick.

Inside, the monumental carved Norman pillars along the nave, feel heavy and dark, recalling Sir Walter Scott’s line about it being ‘half Church of God, half castle ‘gainst the Scot’. Unusually, I don’t linger. I tell myself that’s because I’m concerned for the security of the bike, locked around a drainpipe, but in reality it’s because this solitary me feels slightly less comfortable amid the gaggles – even gaggles partially hushed by the majesty of a holy place. Time instead to take in the wider landscape around Palace Green. Fair play to the visionary bishop – and indeed the wandering cow – it’s a spectacular spot with learned university buildings completing the perimeter. My only disappointment is that the fringes of this ‘summit’ are so wooded that I can’t quite make out the Wear below.

Cycling back down the hill doesn’t feel quite right here. So I compromise, scooting down with a foot on just one pedal ready to jump off if pedestrian traffic gets too heavy. I find the market place, home to the town hall and a ridiculously large statue of the third Marquis of Londonderry – a military man turned coal mine baron from the Victorian era. I then pick up the route the coaches would have taken along Silver Street to the second crossing of the Wear at Framwellgate Bridge. Once you cross, it’s as if the supply of tourists has been abruptly switched off. Here on North Road, Durham feels normal, down-at-heel even. Of course all towns and cities have that slightly more run down street, the one that’s home to the vape stores and the takeaways, but here the contrast seems particularly acute. It’s almost as if the natives have fought a losing battle for their own city and have retreated to the north of the river, determined to make one last stand around the bus station.

For me, the only way is up. Seriously up. I head under the viaduct which keeps the East Coast Main Line out of trouble and continue to climb. Yesterday I would have found it a real struggle, but today I feel as if I could conquer Alpe d’Huez without a problem. Has my body finally adapted to life on the road or is it just one of those days? The Durham of tourists gives way to the County Durham of former pit villages. I move from North Road to Front Street somewhere between Framwellgate Moor and the curiously-named Pity Me – I’m starting to discover that you can traverse most of County Durham without leaving North Roads and Front Streets. There were four pits in this area, Brasside, Framwellgate, Dryburn and Frankland. All were closed before the outbreak of the Second World War, yet all these years on, the lie of the land and the cut of the houses somehow give the game away.

The A167 is about to become a dual carriageway, so I veer east, narrowly avoiding a sewage works with the wonderful postal address of ‘Stank Lane, Pity Me’. Soon I find myself on a country lane, but is it the right road? Three MAMILs are speeding along in the opposite direction, but come to a halt when I hail them. They politely reassure me that I’m heading the correct way, but as they head off, one mutters to the other ‘well, that’s another segment buggered.’ Across the country cyclists use the Strava app to sub-divide every road into ‘segments’ like this. On balance, trying to be the rider with the fastest time along a particular stretch is pretty harmless fun, but sometimes, just sometimes…

Then it’s Chester-le-Street, Barley Mow and Birtley in quick succession as I realise that I’ve come within the gravitational pull of a greater Tyneside. That country lane will prove to be the last for a while. But cycling continues to be easy. There’s plenty of traffic, but there’s invariably a bike lane too.

The A1 lies to the east. Here, Norman Webster called it ‘a magnificent modern highway of bold embankments and wide cuttings which avoids the ugliness of the former scenes and captures the best of the Durham greenery.’ The old road and the new meet at Junction 66 amid much swooping of spur roads. I negotiate those before being confronted with the massive Angel of the North – out of nowhere. You wouldn’t think a celestial being with a 54 metre wingspan could hide in the landscape, but from the south Antony Gormley’s sculpture does just that. Built on the site of pit head colliery baths, it was quickly taken to the hearts of North Easterners after being unveiled in 1998.

Gormley had initially been resistant to the wooing of Gateshead Council, telling them sharply that ‘I don’t do sculptures for motorways’. But the road wasn’t really the point. The council wanted a statement piece – something acknowledging the past, but looking to the future. And once Gormley had visited, he was converted by the lofty location and mining heritage – even comparing it to an Iron Age tumulus.

He took the commission and then set out to immerse himself in the region, taking inspiration from the shipbuilders of the Tyne as well as those who had once earned their living underground, indeed under this ground.

‘The Angel resists our post-industrial amnesia and bears witness to the hundreds and thousands of colliery workers who had spent the last three hundred years mining coal beneath the surface,’ he wrote.

Post-industrial amnesia! Whilst I couldn’t give it a name, that’s exactly the feeling I’d been unable to articulate back at Bentley in Yorkshire where an anonymous ‘community woodland’ struggled to do justice to the pit buildings it had both replaced and erased.

On this windswept bluff overlooking the Team Valley, the Angel took some anchoring. Its foundations are sunk 20 metres deep into the solid rock below. To counter the wind, its wings are tilted slightly inwards – providing a literal protection from the elements and a figurative embrace to the 90,000 drivers who pass by every day.

‘It’s a real symbol of the area,’ says the lady serving drinks at the Coffee Station kiosk.

‘I mean, we’ve got lots of them up here, we’ve got the Tyne Bridge, the Sage, Penshaw Monument, there’s loads. But this is the one you’ll see on the TV.’

I hang around longer than I mean to among a gaggle of visitors doing just the same. And they’re not just long distance ones, three cyclists from Whitley Bay are busy with the selfies too.

The cost of this masterpiece was £800,000. I cycle out of the car park and take one last look over my shoulder. Less than a million pounds, what a complete bargain.

Birtley has become Low Fell which soon becomes Gateshead – and the beautifully smooth bike paths get better and better. As a cyclist I haven’t been treated this well since Stevenage. From Gateshead the contours start to dip drastically toward the Tyne along steep streets that mail coach passengers used to hate. But since those distant days the engineers have thrown spectacular high level bridges across the Tyne valley, saving several hundred feet of descent and ascent in the process.

I think it was this vista which helped me fall instantly in love with Newcastle when I first came here in 1986 for an interview at the university. Arriving by train from the south, you can’t help but be affected by the majesty of the river and the multiplicity of its bridges. There’s no drifting in through faceless suburbs, just one ‘wow’ moment – unmatched by any other city in England. The university was good enough to offer me a place, I ended up living in the North East for eight years and I have trusted my first impressions of cities ever since. So, in a rather self-absorbed way that I had better not bang on about, cycling over the coat hangershaped Tyne Bridge brings a lump to the throat. To begin with I’m even a little nervous that the older me won’t feel the same as the 19-year-old version, but, thankfully, it still takes my breath away. The traffic is incessant, the pollution is probably terrible, but the view is magnificent. Beneath us, the merchants’ houses along the quayside, above, the tall spire of the Georgian All Saints Church before more distant impressions of vigorous retail and commerce. A patch of lime green amid the chimney pots is gradually revealed to be a tiny astroturf roof garden complete with recliners and pot plants. I take endless photos of the bridge, the bike, the city and the river – none of which quite capture the magic of the moment. No doubt the fact that I’m arriving under my own steam is providing its own invisible filter.

To understand Newcastle, you need to know that the city has grown up from the river over the centuries, giving it a multi-layered charm explained beautifully by the architectural critic Ian Nairn:

‘It is built on one side of a hundred-foot gorge,’ he wrote in Nairn’s Towns. ‘And the medieval town struggled up it from the quayside, producing dozens of sets of steps or ‘chares’ which even in their present neglect can produce a kind of topographical ecstasy as you go up and down, perpetually seeing the same objects in a different way.’

Nairn was a maverick who railed against the homogenisation of British architecture in the decades after the war. He coined the phrase ‘subtopia’ to describe the depressing tendency of city hinterlands to lose their identities. Nairn loved Newcastle. Heading up from the quayside, he soon found the neo-classical Grainger Street and Grey Street, roads which ennobled those who walked along them:

‘I mean this literally: there are some places that seem to have the gift of transferring or sharing their qualities with the viewer… The precise quality is grandeur without pomposity; everything serious, but not lugubrious, everything formal and firmly urbane but not oppressive.’

Hear, hear.

The Great North Road: London to Edinburgh – 11 Days, 2 Wheels and 1 Ancient Highway by Steve Silk (Summersdale) is available from all good retailers.