The County Durham Man Who Split the States in the 18th Century

County Durham boy Jeremiah Dixon was a hard-drinking Quaker who led one of the most complex and technically demanding geographical projects of the 18th century – and 250 years on, the Mason-Dixon Line still defines America’s culture wars

‘That’s incredibly interesting and everything,’ you’ve presumably just thought, ‘but beyond being in the North East of a country – and not the one we’re currently in, I would add – what’s it got to do with us?’

A fair question. This year is the 250th anniversary of the completion of the Mason-Dixon Line, and half of its name is given by Jeremiah Dixon of Cockfield, near Bishop Auckland. Along with his collaborator Charles Mason, he helped draw up a line which was intended to define the border between two states, and came to represent a chasm between two cultures.

Jeremiah was born on 27 July 1733, and was the fifth of seven children born to mine owning Quaker Sir George Fenwick Dixon and Lady Mary Hunter. His great-grandfather was called Robertus, which gives you some idea of the kind of family Jeremiah came from. His Newcastle-born mum was said to be the cleverest woman who ever married into the family (though the same account also makes mention of her being ‘of the small shoe’, which is a really odd thing to congratulate a woman on), and Jeremiah inherited her intellect. He went to John Kipling’s School in Barnard Castle and quickly became fascinated by maths and astronomy, though he was less than enamoured with the school itself – later, he told an exam board at the Royal Military Academy that he was schooled in ‘a pit cabin upon Cockfield Fell’.

As well as being fortunate to have a mine-owning baronet for a farther, Jeremiah happened to grow up in County Durham at a time when there were many other very, very handy blokes around the area. William Emerson, a brilliant mathematician from Hurworth (also notable for wearing his shirts back to front and wrapping his legs in sacking to protect them from getting scorched when he sat at the fireside) was a good friend, and he knew the Bishop Auckland mathematical instrument-maker John Bird and natural philosopher Thomas Wright too. For a bright young man with a thing for numbers, there weren’t many better places to be in the mid-18th century.

As a man, Jeremiah seems to have been something of a jumble. While he was a Quaker like most of his family, he did have a weakness for low-grade gin, an affliction which also affected his farther. That’s not gold-star Quaker behaviour – in fact the Quaker Minute Book of Raby notes that on 28 October 1760, ‘Jery Dixon, son of George and Mary Dixon of Cockfield was disowned for drinking to excess; Nor was his apparent habit of parading about in a full military redcoat with a cocked hat. That last longstanding family story turned out not to be true, sadly, but Jeremiah seems to have been the kind of well-built, exuberant, foppish, attention-grabbing young man to whom rumours attached themselves.

It was most likely through John Bird, who was a Fellow of the Royal Society, that Jeremiah got the chance to observe the 1761 transit of Venus along with Charles Dixon. They were due to head to Sumatra in Indonesia and use the data they brought back to work out the distance from the Earth to the Sun.

Annoyingly, the French got in the way – and their ship, the HMS Seahorse, was attacked early on in their six-month voyage by a man-o’-war and suffered such casualties and damage that they had to turn back to Plymouth for repairs. Jeremiah and Charles, who’d never seen battle before, were presumably very annoyed about not being able to get to Sumatra in time, but headed instead to the Cape of Good Hope and built a temporary observatory, and Jeremiah later returned to the Cape to work on experiments with gravity.

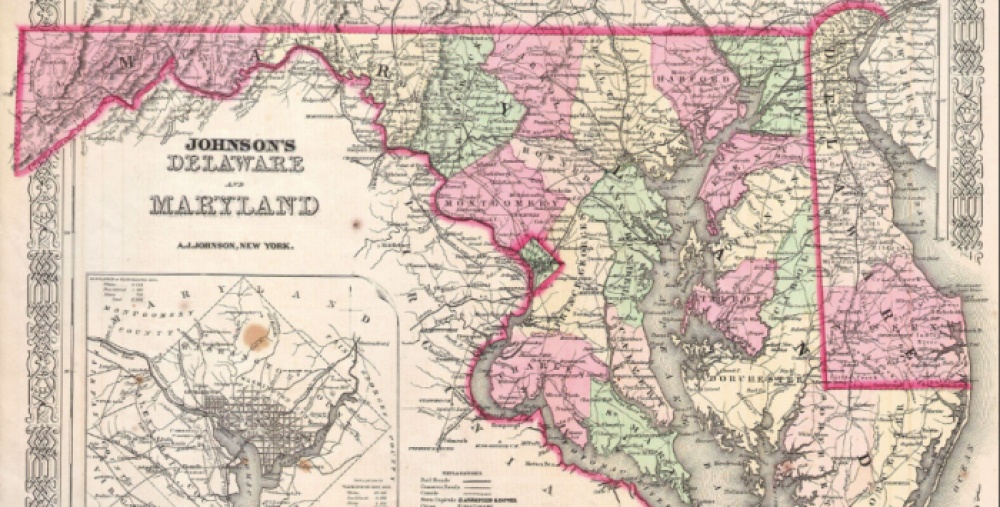

Then, in 1763, Thomas Penn and Frederick Calvert came calling. The former was the largest private landowner in the world at the time, and the proprietor of the state of Pennsylvania; the latter owned Maryland. They needed the border between their two states sorting out – there had been vociferous disputes over land from the Delaware River westward since about 1681 – and it had proved to be beyond the skill of the American surveyors they’d hired.

Drawing the line itself was not simple. Jeremiah and Charles’ task was, if you’ll bear with us a second, to work out the tangent line north from the easternmost point of the line, then work out the boundary running laterally 15 miles south of the southernmost part of Philadelphia. If that sounds complicated, that’s because it is.

It took the best part of five years to trace the line and map it, even using the most advanced astronomical equipment available. They used a telescope wth crosshairs and precise adjustment screws to find exactly horizontal points, and used it to find true north by tracking stars to where they crossed the meridian while using a ‘zenith sector’, a six-foot telescope mounted on a six-foot radius protractor, to measure the angle at which they crossed the meridian. They pulled it about on a mattress in a cart. As well as that, they had to hack through miles and miles of virgin forest and lay down posts which had been brought from England marking the line as they went.

Things were politically fraught too. The two men arrived on 15 November 1763, at a point when colonists and Native Americans fought brutally. A French-backed attack by the Ottawa people on Fort Detroit on 5 May that year killed 200 people, and a vengeful mob of Scottish and Irish migrants attached a small village of Native Americans in Lancaster, Pennsylvania that December, hacking and scalping their victims.

It was an extremely tense time, and both men were shocked by the violence they saw. One day while tracing the line, Jeremiah came across a slaver beating a black woman. Incensed, he demanded that the slaver stop. The slaver told him to mind his own business.

‘If thou doesn’t desist I’ll thrash thee!’ Jeremiah snapped. The slaver did not desist, so Jeremiah grabbed the slaver’s whip out of his hand and chased him around with it, giving him, biographer HW Robinson notes, ‘the sound thrashing that he richly deserved’. Jeremiah kept the whip as a trophy and took it home with him to Cockfield. Again, not very Quakerly, but you can’t imagine God having too much of a problem with this slightly agricultural application of swift justice.

The project came to an abrupt end in 1767, when Jeremiah and Charles’ Mohawk guides declined to go any further as they were crossing into a rival group’s territory. Later surveyors managed to finish what they started, though, and the line’s significance began to blossom. It became the division between the slaving south and the free north after Pennsylvania abolished slavery, and a profound psychological and cultural barrier which is still central to understanding America. Jeremiah Dixon inadvertently gave his name to ‘Dixie’, the nickname for the Confederate states. Given his Quaker background and violent disavowal of slavery, he’d probably have been utterly devastated.

For his work, though, Jeremiah was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1773, and retired to potter around Cockfield before dying in 1779, aged 45. His greatest achievement wasn’t referred to as the Mason-Dixon Line publicly until about 1820 so he went to his grave unaware of the extent of the impact he had had on American life, but this County Durham lad’s influence is very much there today – written into the land itself.