Is There Life on Mars?

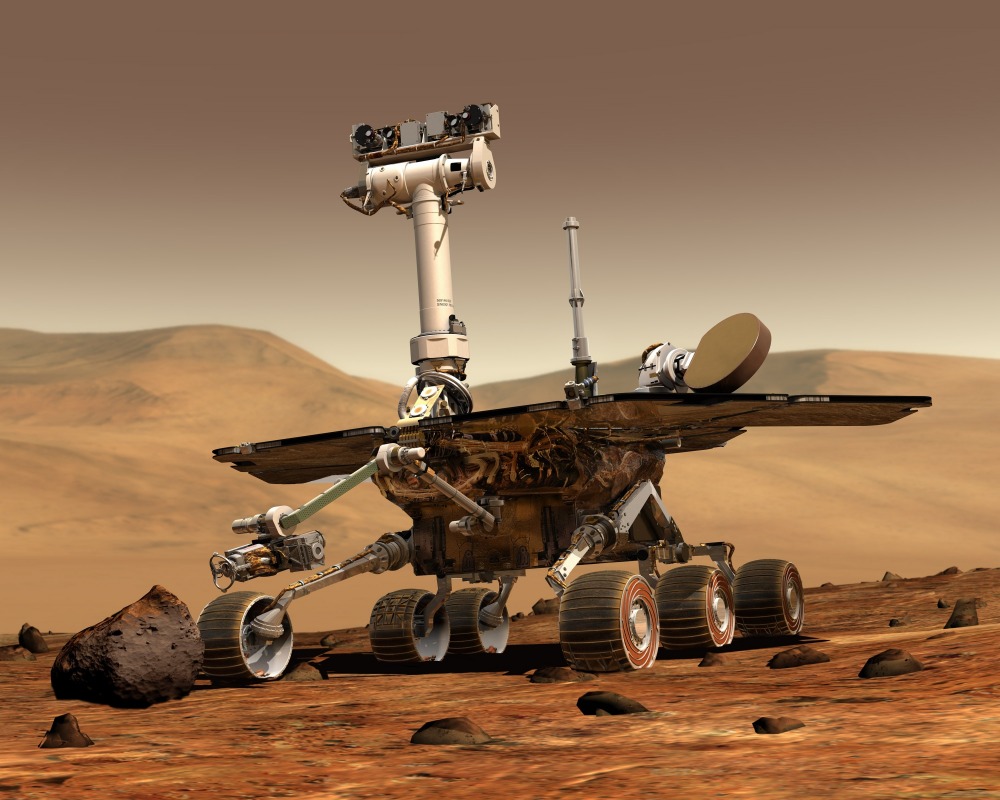

With Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson recently completing their pioneering space flights, it seems the hype about future space tourism is at the forefront of many people’s minds. NASA’s Perseverance Rover landed on Mars in February and has been transmitting data throughout the year, and Elon Musk’s SpaceX is working on plans to put humans on the red planet by 2026, which leads us to David Bowie’s (and now Yungblud’s) often-asked question: is there life on Mars?

There’s no better person to ask than Dr Simon Morden who recently published his book The Red Planet: A Natural History of Mars. Simon trained as a planetary geologist and geophysicist, but when he realised he was never going to get into space himself, he decided to write about it. His new book takes you through the history and geology of Mars, and pieces together the latest research and data from the Mars probes (along with some pretty bizarre theories about the planet).

‘I was just three when the first moon landings took place,’ Simon tells us. ‘My parents sat me down in front of a black and white television to watch it. I can’t remember it, unfortunately, but I can remember the little models you could get in cornflakes. Since then, I’ve always been interested in space.

‘After studying a degree in Geology in Sheffield I moved to Newcastle, initially to do a masters in Geophysics, but I got the opportunity to transfer to do a PhD which I finished in 1990. Nasa have a big book of meteorites and you can write to them and ask to access some to experiment on. I got hold of one of the meteorites to experiment on, but none of my experiments were turning out right. I was very confused and decided to leave that and move on. It was long after I’d sent the meteorite back to America that I discovered that the reason why none of my experiments were giving me the right results was because it came from Mars, not from the asteroid belt. That was it. I’d missed my opportunity. If I had realised 30 years ago, I would really have discovered something. Mars has been hanging over my head for 30 years as a missed opportunity.’ That’s why Simon decided to write this book.

‘Mars has always been an object of fascination, from the earliest point of time when people looked up to the sky and saw a red point of light,’ he explains. ‘It’s simply been about our technical capabilities to get there. The ability to put things on Mars has been increasing year on year – and we can do it reliably now. It’s not just the big players in America and China either; India have put a probe in orbit as well. There’s a certain amount of prestige to be able to do this so people are perhaps showing off, but it does mean that scientists get some good information out of it as well, which is a win for us.’

It’s that research which allowed Simon to tell the story of Mars, and he hopes readers will learn plenty from it. Since its formation 4.5 billion years ago, Mars has continued to change (cataclysmic meteor strikes, explosive volcanoes and a vast ocean that spanned the entire upper hemisphere have all had an impact), and as we’ve been able to see more of Mars over the years, plenty of theories have emerged about the planet and its moons (some of which are among the smallest in the solar system). ‘One of my favourite theories was started off by a Russian scientist in the 1950s,’ Simon reveals. ‘One of the Martian moons, Phobos, is a strange shape and weight so he proposed, quite seriously, that it was an alien spaceship. If you take its size and shape, it was believed that Phobos could be hollow. It wasn’t until decades later that someone was able to disprove this and prove that Phobos was actually just made of a very light rock, rather than being an alien artefact.

The other theory I like is whether there’s actually a face on Mars. There is an image of Mars with what looks like a pyramid with a face on top. People went bananas about this, stating that aliens must have landed there and made a giant pyramid with a face so that, when we see it, we’ll know they’ve been there. Unfortunately, that’s not true either. If you take images of the same area, at a better resolution and in different lighting, the image goes away almost completely. The human mind always looks for shapes and faces in whatever it sees – in the same way that we see faces in rocks and gnarly trees. We automatically make patterns out of what we see.’

Just because many theories have been debunked, doesn’t mean there’s no life on Mars. Simon argues: ‘It’s certainly too soon to say there isn’t life on Mars. I don’t think there is now. In the past, when Mars had an ocean (which it certainly did at one point), the conditions were very similar to those on earth, when our own life evolved billions of years ago. I would hold out for there having once been life on Mars, and

I think we will eventually find evidence of that.’ But to find that evidence we’re going to need more research, and Simon’s book is a good place to start. ‘I wanted to try and explain Mars on its own terms, as if it was telling its own story,’ he says. ‘Mars is as unique as the Earth, and just because it looks like it’s dry and dusty at the moment, I wanted to bring it to life with its own story by describing its formation and its history in a way that will make people appreciate the planet for what it is (or was), rather than it being somewhere we can go and potentially make as much of a mess of as we have our own planet. It’s possibly a second chance to get it right – to treat a planet with a bit of respect.’

That respect is just as important when it comes to future research. ‘We need to talk about what we want to do with Mars before we actually get there,’ Simon adds. ‘Are we going to try and save it for scientific purposes in the same way that we saved Antarctica?

We’re going to put people on Mars, and that’s inevitable, but I would much rather people came and went and did their research and brought back their samples. What I would want from it is some sort of Mars Treaty, in the same way we have The Antarctic Treaty, to protect Mars from being exploited.’