Branwell Brontë: Meet the Forgotten Brother of Charlotte, Emily and Anne

Two hundred years ago this June, Branwell Brontë was born

On 1 June 1846, a traumatised, heartbroken young man wrote the saddest of poems about doomed love. ‘On Ouse’s grassy banks last Whitsuntide / I sat, with fears and pleasures in my soul / co-mingled, as it roamed without control / o’er present hours and through a future wide / where love, me thought, should keep my heart…’

The poem quickly turned darker in tone. ‘But as I looked, descended summer’s sun, and did not its descent my hopes deride? / The sky, though blue, was soon to change to grey…’ And then, the poet Branwell Brontë might have added, to black. For the lights were already going out on his short and ill-fated life.

So who was the woman who inspired those lines and, many believed, precipitated Branwell’s descent into drug dependency and chronic alcoholism, which led to his tragically early death? Branwell scrawled her name, in large Greek letters, at the top of the poem: Lydia Gisborne.

Gisborne, however, was her maiden name. Unfortunately for Branwell, she had long been married to the Reverend Edmund Robinson, the wealthy owner of Thorp Green Hall at Little Ouseburn, near York. More than three years before, aged 25, Branwell had gone to live at the house to be tutor to the Robinsons’ youngest child, a son also named Edmund. He promptly fell in love with Mrs Robinson, who was much older – probably 43 – and already a mother of five. It is very likely, but not absolutely certain, that they became lovers.

Read More: Living North Chats with Brontë Expert Nick Holland

Either way, Lydia, like Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby, was careless with her love and ultimately indifferent to Branwell’s infatuation. When he was sacked after two years in 1845 for being ‘bad beyond expression’, Lydia never made any effort to see him again. He returned home to The Parsonage in Haworth, a broken man, sinking into a deep depression and immersing himself in self-pity, alcohol and opium.

This terrifying journey of self-destruction was expertly, if not rather chillingly, charted in Sally Wainwright’s brilliant biopic, To Walk Invisible, which was shown on BBC One over Christmas, as we watched Branwell (played by Adam Nagaitis) wrestle his demons to the dismay of those around him. But it would be too simplistic to blame Branwell’s decline solely on Lydia Robinson – the seeds of his tragedy had been sown much, much earlier.

Born in June 1817, he was the second child (after Charlotte) of the Reverend Patrick and Maria Brontë. Unlike his sisters (Charlotte, Emily and Anne), Branwell was tutored at home at Haworth Parsonage. The only brother in a family of sisters, he was the indulged, spoiled darling of the family. But he was also, like his sisters, highly talented.

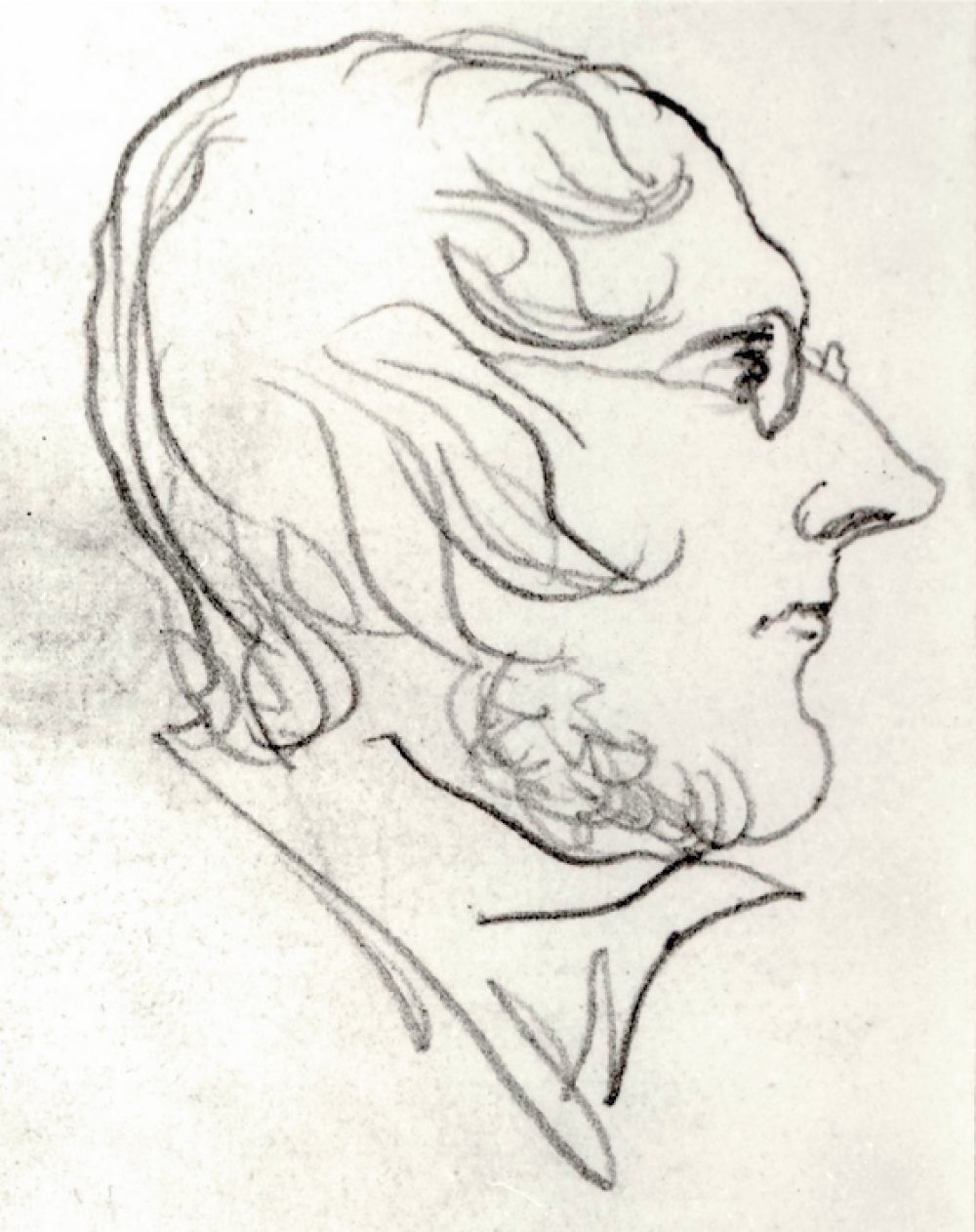

A willing scholar with a precocious intellect, Branwell translated Horace to critical acclaim, wrote poetry, played the organ in his father’s church and aspired to being a professional portrait painter. The young siblings were incredibly close, living in a very personal world fired by their imaginations. Within this world, the adolescent Branwell was king.

Read More: 25 Great Things We Love About Yorkshire

Physically small, he had flaming red hair, was impulsive and quick-witted, and had ‘penchant for showing off in company’, according to the Brontë Society’s biography. However, he also had an erratic and emotional nature that stopped him making the most of his talents. Even before his disastrous job at Thorp Green, he had failed as a portrait painter, been sacked from a job as tutor with a family in Westmoreland and then dismissed as clerk-in-charge at Luddenden on the Leeds-Manchester railway for having missed a discrepancy in the accounts. Crucially, he didn’t have the mental resources to counter rejection.

Daphne du Maurier, in her definitive biography, The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë, writes: ‘The seeds of Branwell’s destruction lay not just in his doomed love affair, but also his inability to distinguish truth from fiction and reality from fantasy. He failed in life because it differed from his own infernal world.’

Meanwhile the Yorkshire poet Simon Armitage, who is leading the celebrations for the 200th anniversary of Branwell’s birth commented: ‘Most people know Branwell either as the ne're-do-well brother of the Brontë family or as the shadowy absence in his famous portrait of his three sisters. We'll never really know Branwell properly, but in putting together events for his bicentenary I feel as if I've been privy to some of his hopes and dreams.’

For Simon, there is far more to the story of the forgotten Brontë than we’ve truly understood. ‘Branwell's early promise and swaggering enthusiasm was ultimately overshadowed by the talents of his siblings,’ he remarks, ‘but even before then he appears to have lost his boyish optimism and fighting spirit, and I've found it impossible not be saddened by his disillusionment and decline.’

‘As a poet of this landscape and region I recognise Branwell’s creative impulses and inspirations,’ he explains. ‘I also sympathise with his desire to have his voice heard by the wider world – a desire encapsulated in a letter sent to William Wordsworth in 1837, when Branwell was a precocious and determined 19 year old, seeking the great man’s approval. The poem he enclosed describes the dreams and ambitions of a young and hopeful romantic, star-struck by the universe and building “mansions in the sky”. But those mansions were only ever hopeful fantasies, and Branwell was to die unrecognised and unfulfilled, forever assigned the role of the dark and self-destructive brother, doomed to be eclipsed by the stellar achievements of his sisters.’

The symbolic heart of the fraught and ultimately toxic relationship between Branwell and Charlotte, Emily and Anne is Branwell’s painting of his three porcelain-skinned sisters. Branwell – the failed artist, poet and scholar of Greek; the sacked railwayman, dismissed tutor, disgraced debtor and local drunk – initially included his own likeness and then painted himself out with a pillar. Mirroring this fragility of spirit was Branwell’s abortive attempt to take his paintings to the Royal Academy in London in 1835; he only got as far as Leeds, where he embarked upon a mighty bender.

‘I know only,’ Branwell wrote in 1847, the year before he died, ‘that it is time for me to be something when I am nothing.’ There was, recorded Charlotte, an ‘emptiness’ to his ‘whole existence’.

By 1847 Branwell was living on borrowed time. The death of Mr Robinson of Thorpe Green gave him hope in his fevered imagination that he could rekindle his relationship with Lydia, but she had moved on, now caring little for the flame-haired tutor who had once beguiled her. Rebuffed, he sought sanctuary in alcohol and opium, rarely leaving his room at the Parsonage. He began begging friends for money for alcohol, embarrassing his family and even once set fire to his own bed, requiring his father Patrick to share a bed with him to protect the family.

There is a school of thought that his deep depression, fuelled by insecurity and low self-esteem, was exacerbated by the success of his sisters, whose novels Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey were coincidentally published to great acclaim in 1847. This is unlikely. As Charlotte explained: ‘We could not tell him of our efforts for fear of causing him too deep a pang of remorse for his own time misspent, and talents misapplied.’ In any case, Branwell’s world was now such a strange mixture of fact and fantasy that the news that all his three sisters had had novels published, under male pseudonyms, would surely have baffled and confused him.

Branwell died at home on 24 September 1848. He was just 31. While his cause of death was recorded as ‘chronic bronchitis-marasmus’, most now believe that he died from acute tuberculosis aggravated by alcoholism, drug use (specifically opium and laudanum) and alcohol withdrawal, aka delirium tremens. He was placed in the family vault four days later. His father, who had tried so hard to halt his beloved son’s tragic decline, was inconsolable.

His elder sister Charlotte, whose acute insight into human nature gave her a special understanding of her brother’s torment, wrote three weeks after his death: ‘When I looked upon the noble face and forehead of my dead brother, I seemed to receive an oppressive revelation of the feebleness of humanity; of the inadequacy of genius to lead to true greatness.’ It was a terrible lesson to learn.

Within two years of penning his sorrowful ode, Branwell Brontë, one of the most tragic figures of an era littered with literary casualties, having struggled and struggled to swim in woe’s far deeper sea, had sunk.